Amy and Diedra are best friends, maybe more, something always seems to be in the way every time an opportunity to explore the possibilities arise. Dave Plasko is serving a long sentence at Huntsville state prison, and after that he will be transferred to New York to serve more time. Rebbeca Monet is working her way up the ladder of success in the television reporter game. A hurricane of epic proportions is heading towards Mobile Alabama. The lives of the people involved will never be the same again… #Crime #Drama #Action #Readers #DellSweet #KDP #KU

The Nation 07

Series: The Nation, Book 7

by Dell Sweet

A crash came to his ears, but he could not tell if it was from the downstairs hallway. At least he hoped it was the downstairs hallway, not the stairs outside of their apartment, or, God forbid, even closer. He jumped from the tangle of blankets, started to pull his shoes on, and then reached for his machine pistol instead as another noise came from the hallway. #Horror #Series #Dystopian #Apocalyptic

https://books.apple.com/us/book/x/id720207183

Dell Sweet on Apple Books https://books.apple.com/us/author/dell-sweet/id722382569

Home: https://www.wendellsweet.com

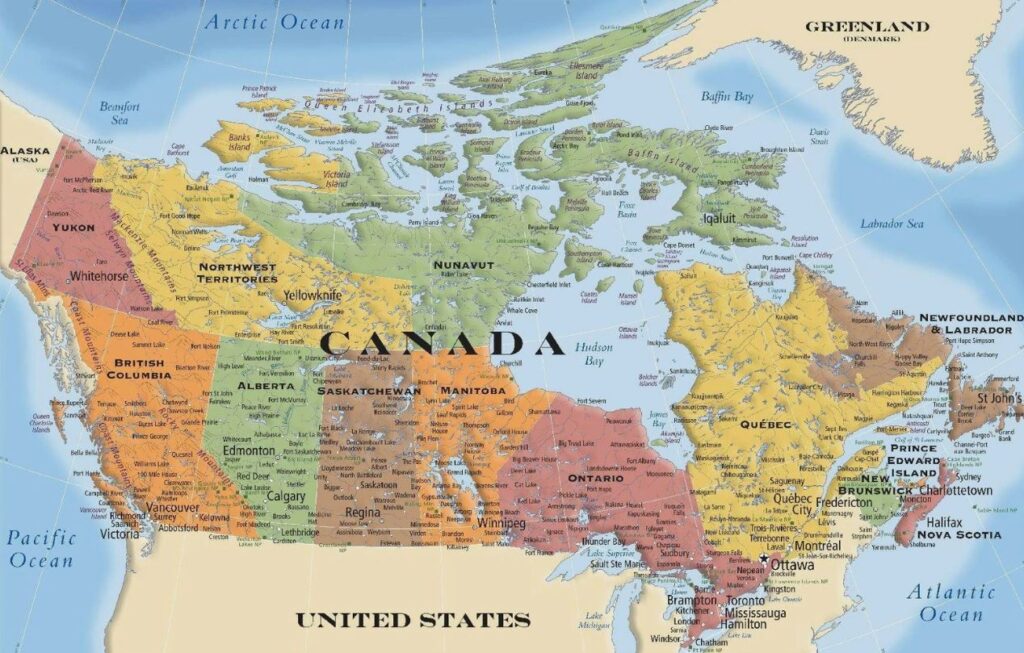

Canada is a large North American country that is a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy. It has a unique history shaped by both French and English colonization, and its close relationship with the U.S. is occasionally marked by disagreements.

How Canada Became a Country

Canada’s formation was a gradual process, often described as an evolution rather than a revolution:

- Early History: The land that is now Canada was originally inhabited by diverse Indigenous peoples for thousands of years.

- European Colonization: Starting in the 16th century, the land was colonized by both French and British explorers. The French established New France along the St. Lawrence River (modern Quebec).

- British Conquest (1763): Following the French and Indian War (part of the Seven Years’ War), France was defeated and ceded almost all of its North American territory to Great Britain in the Treaty of Paris (1763). This effectively placed all of Canada under British rule.

- Confederation (1867): On July 1, 1867, the British North America Act was passed by the British Parliament. This act united three British colonies—the Province of Canada (now Ontario and Quebec), Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick—into a single entity called the Dominion of Canada. This created a self-governing federal state, though it remained part of the British Empire.

- Full Independence (1982): Canada’s final step toward full legal autonomy came in 1982 with the repatriation of the Constitution (the Canada Act 1982), which severed the last legal ties to the British Parliament.

Why Canada is Part French and Part English

The country’s bilingual nature is a direct consequence of its colonial history:

- French Legacy: The French were the first to establish major permanent settlements in the early 17th century. Even after the British conquest, the Quebec Act of 1774 guaranteed the French-speaking population the right to maintain their French civil law, Catholic religion, and language. This preserved a distinct French-Canadian culture.

- British Dominance: The majority of the rest of the land was settled by English speakers, primarily from Great Britain and later by Loyalists who fled the American Revolution.

- Official Bilingualism: The Constitution Act of 1867 formally recognized both languages for use in the federal Parliament and courts. Today, the Official Languages Act (1969) makes English and French the two official languages, ensuring all federal services are available in both. Quebec remains the only officially French-only province (for provincial institutions), while New Brunswick is the only officially bilingual province.

Disagreements with the United States

While the U.S. and Canada share the world’s longest undefended border and are close allies (including through NATO and NORAD), disagreements occasionally arise, often due to Canada’s desire to maintain its autonomy in the shadow of its much larger neighbor:

- Trade Disputes: Disagreements frequently occur over trade and tariffs on specific goods, such as timber, steel, and agricultural products. The management and interpretation of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) is a constant source of friction.

- Cultural Sovereignty: Historically, Canadians have been sensitive to the overwhelming influence of American culture and media. This has led to policies intended to protect Canadian cultural industries (e.g., funding for Canadian content).

- Foreign Policy Differences: While often aligned, Canada has at times refused to join U.S. military actions, most notably refusing to participate in the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Canada’s Form of Government

Canada is neither a pure democracy nor a theocracy; it is a complex form of representative governance:

- Parliamentary Democracy: Canada operates under a parliamentary system based on the Westminster model. Citizens elect members of Parliament, and the political party with the most seats forms the government, led by the Prime Minister (the head of government).

- Constitutional Monarchy: The King of Canada (currently King Charles III) is the head of state. However, his power is largely ceremonial and exercised on the advice of the government. The King’s representative in Canada is the Governor General.

- Federal State: Power is divided between the federal government (responsible for national issues like defense, trade, and banking) and ten provincial governments (responsible for areas like health care, education, and property rights).

Home: https://www.wendellsweet.com

The Nation 06

Series: The Nation, Book 6

by Dell Sweet

Beth levered her arms down to scoot up in the bed and nearly banged the stump of her arm against the side of the bed before Cammy stopped her. “Honey… Honey… Your arm. You have to be careful,” Cammy told her. “Oh God,” Beth whispered through her dry lips as she stared down at the stump of her arm. #Horror #Series #Dystopian #Apocalyptic

https://books.apple.com/us/book/x/id917485796

Dell Sweet on Apple Books https://books.apple.com/us/author/dell-sweet/id722382569

Home: https://www.wendellsweet.com

The Nation 05

Series: The Nation, Book 5

by Dell Sweet

There were four of them outside the vehicles talking or keeping watch on the parking lot. Bear and Beth, Mac and Billy. When the first one dropped, Billy spun around and clubbed it to the ground. But the rest came so fast that they could not hope to easily and quickly pick them off.

#Horror #Series #Dystopian #Apocalyptic

https://books.apple.com/us/book/x/id634567737

Dell Sweet on Apple Books https://books.apple.com/us/author/dell-sweet/id722382569

Home: https://www.wendellsweet.com

France: The “Oldest and Most Complicated” Ally

France is often referred to as America’s “oldest ally,” a relationship dating back to its crucial support for the American Revolution in 1778.1 Yet, despite this deep historical bond and shared values of democracy and liberty, there’s a recurring perception—particularly in the United States—that France is not always a good or reliable ally.2 This feeling stems not from a failure to cooperate, but from France’s fierce commitment to strategic independence and its history of prioritizing its own national and European interests over American foreign policy consensus.3

This dynamic of cooperation mixed with occasional confrontation has defined the Franco-American relationship for centuries.

The Root of the Tension: Strategic Autonomy

The fundamental reason France is often perceived as a “difficult” partner is its pursuit of “strategic autonomy.” This doctrine is rooted in the country’s post-World War II desire to reclaim its great power status and ensure its security is never wholly dependent on another nation, even a friendly one.5

This drive for independence has been most clearly defined by two major actions:

- De Gaulle’s NATO Withdrawal (1966):6 Under President Charles de Gaulle, France famously withdrew from NATO’s integrated military command structure (though it remained a political member of the alliance).7 De Gaulle evicted all foreign troops and NATO bases from French soil, insisting that France develop its own nuclear deterrent (force de frappe). This was a clear message that France would determine its own defense policy and would not automatically submit to American military leadership.8

- A Truly European Defense: France remains the EU country that most aggressively champions a truly independent European industrial and defense policy.9 While cooperating closely with the U.S. and NATO on specific missions (like counterterrorism), French leaders, particularly Emmanuel Macron, have consistently argued that Europe must avoid becoming a “vassal” of the United States, especially given shifts in American politics and foreign policy.10

High-Profile Disagreements and Diplomatic Splits

While cooperation on trade, intelligence, and culture is robust, the perception of France as a “difficult” ally is reinforced by several key diplomatic splits:

1. The Iraq War Opposition (2003)11

The most significant modern rift occurred when France, led by President Jacques Chirac, vehemently opposed the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq.12 France threatened to use its veto in the UN Security Council against a resolution authorizing military force, effectively blocking international legal consensus for the war.13

- Consequences: This opposition led to a wave of “Francophobia” in the United States, epitomized by calls to boycott French goods (like wine) and the absurd, temporary renaming of “French fries” to “Freedom fries” in some US government cafeterias.14 The diplomatic fallout strained the alliance for years.

2. The AUKUS Submarine Debacle (2021)

A recent and painful blow to the French alliance was the AUKUS security pact between the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.15 The deal saw Australia abruptly cancel a multi-billion dollar conventional submarine contract with France in favor of acquiring U.S. nuclear-powered submarines.16

- The Snub: France was not consulted and viewed the move as an extraordinary act of betrayal and a diplomatic “stab in the back” by its allies. President Macron temporarily recalled the French ambassador from Washington—a rare and severe diplomatic rebuke—underscoring the feeling that the U.S. prioritizes its own geopolitical interests, even at the expense of its “oldest friend.”17

Historical Context of Complications

The current tensions are not new; they follow a pattern of cooperation and conflict that extends across centuries:

| Historical Point of Friction | Description |

| Quasi-War (1798–1800) | Shortly after their initial alliance, tensions over U.S. neutrality in the French Revolutionary Wars led to French seizures of American ships, resulting in an undeclared naval war. |

| The Suez Crisis (1956) | The U.S. and the Soviet Union jointly opposed the invasion of Egypt by the U.K., France, and Israel. France viewed the U.S. action as a humiliation and a clear example of America undermining its core allies to serve its own global agenda. |

| Vietnam War | De Gaulle’s France openly and vocally criticized American involvement, urging the U.S. to withdraw. |

In short, the feeling that France is a “difficult” ally is an unavoidable consequence of its determination to be a great power in its own right—one that reserves the right to disagree with Washington on matters of global order, trade, and military strategy. For France, being a loyal ally doesn’t mean being an obedient one.

Home: https://www.wendellsweet.com

The Nation 04

Series: The Nation, Book 4

by Dell Sweet

“Beth!” Billy screamed from behind her. “Right. Your right!” She had been just about to fire at the two zombies attacking Mac, and so even as she turned, she did not turn her pistol completely, but kept it aimed to the front towards Mac and the two zombies. By the time she registered how close the three zombies were to her, there was no time to turn the pistol and fire. #Horror #Series #Dystopian #Apocalyptic

https://books.apple.com/us/book/x/id1278635477

Dell Sweet on Apple Books https://books.apple.com/us/author/dell-sweet/id722382569

Home: https://www.wendellsweet.com

The Nation 03

Series: The Nation, Book 3

by Dell Sweet

The rusty hinges of the dilapidated shack groaned a mournful protest as Bear pushed open the door, the scent of damp earth and decay clinging to the air like a shroud. Inside, Winston lay huddled beneath a threadbare blanket, his breathing shallow and ragged. #Horror #Series #Dystopian #Apocalyptic

https://books.apple.com/us/book/x/id1245409334

Dell Sweet on Apple Books https://books.apple.com/us/author/dell-sweet/id722382569

Home: https://www.wendellsweet.com

The Nation 02

Series: The Nation, Book 2

by Dell Sweet

The sun, a weak, watery orb, struggled to pierce the perpetual gloom of the junkyard. Its rays, filtered through the grimy haze of industrial decay and the skeletal remains of rusted cars, cast long, distorted shadows that danced with the shuffling figures of the undead. This was their sanctuary, a chaotic landscape of twisted metal, shattered glass, and the lingering stench of decay – their home. #Horror #Series #Dystopian #Apocalyptic

https://books.apple.com/us/book/x/id712828059https://books.apple.com/us/book/x/id712828059

Dell Sweet on Apple Books https://books.apple.com/us/author/dell-sweet/id722382569

Home: https://www.wendellsweet.com

The Conflict: North Versus South

The Vietnam War (known in Vietnam as the Resistance War Against America or simply the American War) was primarily a conflict between the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), led by Ho Chi Minh and his successors, and the anti-communist Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), backed initially by France and later by the United States.

- North Vietnam sought to reunify the country under a single communist government. Their forces included the regular People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the Viet Cong (VC)—a South Vietnamese communist guerrilla force supported by the North.

- South Vietnam sought to maintain its independence as a non-communist state. Their primary military force was the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), heavily supported by U.S. troops and materiel.

The conflict was a major proxy war of the Cold War, with the North supported by the Soviet Union and China, and the South supported by the United States and other anti-communist allies.

French Involvement First (The First Indochina War)

French involvement was rooted in nearly a century of colonial rule over Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia).

- Colonial Resistance: Following World War II and the Japanese occupation, the French attempted to re-establish their colonial control, but they were met with fierce resistance from the Viet Minh, a nationalist and communist-led independence movement under Ho Chi Minh.

- The Defeat: The war between the French and the Viet Minh lasted from 1946 to 1954. The decisive turning point came with the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, where the French forces were decisively defeated.

- The Geneva Accords (1954): This agreement formally ended French rule and temporarily partitioned Vietnam at the 17th Parallel. The North would be governed by the Viet Minh, and the South by a non-communist regime. Crucially, the accords called for nationwide unification elections in 1956, which were ultimately rejected by the South Vietnamese government (with U.S. backing) because they feared Ho Chi Minh would win. The division became permanent, setting the stage for the Second Indochina War (the Vietnam War).

American Involvement Afterwards (The Vietnam War)

U.S. involvement grew out of the Cold War policy of containment—preventing the spread of communism.

- Advisory Role (1950s–Early 1960s): The U.S. initially provided financial and military aid to the French and then to the new South Vietnamese government, installing a series of political leaders, most notably Ngo Dinh Diem. The U.S. presence consisted mainly of military advisors and trainers.

- Escalation (Mid-1960s): Following the Gulf of Tonkin Incident in 1964 and the subsequent resolution by Congress, President Lyndon B. Johnson dramatically escalated the U.S. commitment. This marked the shift from an advisory role to large-scale military intervention, including bombing campaigns against North Vietnam and the deployment of hundreds of thousands of combat troops to the South. At its peak, the U.S. had over 500,000 troops in Vietnam.

- De-escalation and Withdrawal (Late 1960s–Early 1970s): The 1968 Tet Offensive, though a military defeat for the North, was a psychological and political victory that eroded American public support for the war. President Richard Nixon introduced the policy of Vietnamization, gradually withdrawing U.S. troops while simultaneously training and equipping the ARVN to take over the fighting.

- End of War: The Paris Peace Accords were signed in January 1973, leading to the final withdrawal of U.S. combat forces. Fighting continued between North and South Vietnam until April 30, 1975, when North Vietnamese forces captured Saigon, leading to the total collapse of South Vietnam and the reunification of the country under a single communist government.

How many American men (and women) died in that undeclared war?

The total number of U.S. military fatal casualties is 58,220. This figure includes men and women from all branches of the armed services who were killed in action, died from wounds, or were missing in action and declared dead. This number is inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C.

How were returning men and women, U.S. Soldiers, treated by the American press and public?

The treatment of returning Vietnam veterans was markedly different from the heroes’ welcomes of previous wars like World War II. It is widely considered one of the most painful legacies of the conflict.

- The Press: Television news brought uncensored, graphic images of the war’s brutality and futility directly into American homes. As the press became increasingly critical after major events like the Tet Offensive, the negative narrative about the war often spilled over onto the soldiers themselves. Negative stories focused on drug use, low morale, and atrocities.

- The Public: Veterans often returned home to an indifferent or, in some cases, hostile public. The widespread unpopularity of the war meant that anger at the policy and the conflict was often conflated with anger at the soldiers who executed it.

- Unlike World War II veterans who received triumphant ticker-tape parades, Vietnam veterans often arrived back individually at quiet airports and were urged to change into civilian clothes quickly.

- While the image of veterans being “spit on” has become a powerful and politically useful myth, evidence suggests such incidents were rare. However, what was widespread was a distinct lack of recognition, gratitude, or organized celebration.

- Many veterans also struggled with the long-term psychological and physical effects of the war, including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which was not widely understood or formally recognized by the medical and veterans communities until years later.

Has it been rebuilt yet? How is Vietnam now…

Rebuilding and Economic Status:

- Economic Reform (Đổi Mới): The initial years after reunification (1975–1986) were characterized by economic struggles due to the imposition of a centrally planned, socialist economy, internal political repression, and a U.S. trade embargo. In 1986, the Communist Party of Vietnam introduced sweeping economic reforms known as Đổi Mới (Renovation).

- Current Status: Vietnam has undergone a remarkable transformation. It has shifted from one of the world’s poorest countries to a lower-middle-income country with a dynamic, market-oriented economy. It is now a major global manufacturing hub and is largely considered rebuilt, economically speaking, having integrated fully into the global economy.

Is it a free country now?

Political Status:

- Vietnam is not considered a free country by international standards; it is a one-party state ruled by the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV).

- While the constitution guarantees fundamental rights, in practice, the CPV maintains tight control over political life, the media, and religious organizations.

- The government has cracked down on dissent and limits freedoms of expression and assembly. While economic and social life is much more open than in the post-war decades, the political system remains authoritarian.

In summary, Vietnam is a nation that is economically thriving and fully rebuilt, but it operates under a centralized, single-party political system that restricts democratic freedoms. Relations with the United States are robust and have transitioned from adversaries to increasingly strategic partners.